Today in History: the Ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment

Civil Rights Bill Passes, 1866 by Allyn Cox.

Civil Rights Bill Passes, 1866 by Allyn Cox.

During Reconstruction, the period after the Civil War, Congress debated the rights of former slaves and what would happen to those rights in the former Confederate states. Republicans were especially concerned about the increase in congressional representation that the amendment would create in the overwhelmingly Democratic Southern states. Previously, slaves had counted as three-fifths of a person; once granted citizenship, the black population would increase by two-fifths, which would significantly increase these states’ share of congressman in the House of Representatives. While the Republicans wanted to confer citizenship on the former slaves, they also wanted to ensure that the black population would be able to vote to prevent the Democrats from winning all of the new seats. They were worried about voting and other rights for blacks because directly after the war many former Confederate states passed Black Codes which applied to former slaves restricting their movement, limiting their legal rights and forcing them into long term labor contracts–essentially trying to reimpose some of the conditions of slavery.

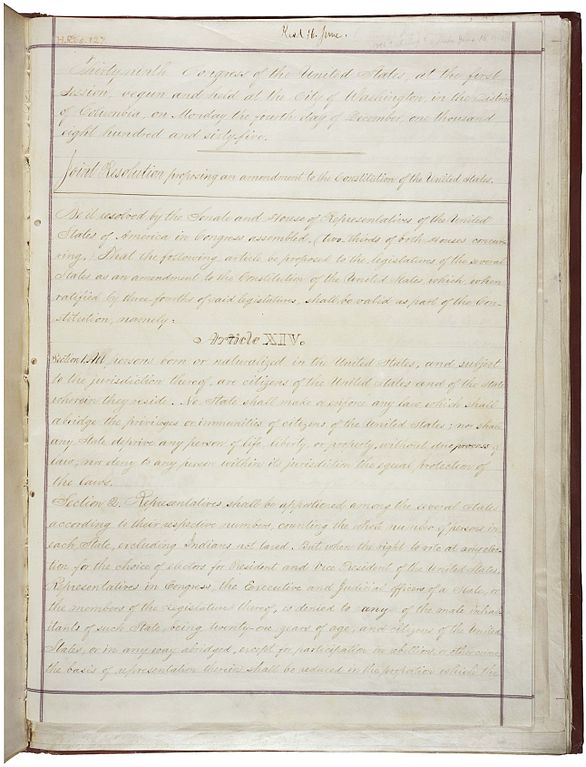

Congress attempted to address this with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, a bill that guaranteed citizenship regardless of color and previous condition of servitude as well as equality before the law. The bill acted as a direct assault on Black Codes passed during the Reconstruction Era to keep recently freed men and women in the same conditions they lived in during slavery. However, even though this bill passed it had to override a veto from President Andrew Johnson, which he had exercised because only 25 of the 36 states were represented in Congress at the time and he believed it favored blacks over whites.

The Civil Rights Act’s narrow passage revealed to radical and moderate Republicans that these objectives needed to be constitutionalized; they were unsure whether the federal government had the authority to dictate these conditions to states and did not believe these rights should subject to the whims of Congress. To do so, they drafted over seventy proposals for the amendment. An early proposal suggested that people prevented from voting would not be counted toward representation; that was blocked by Radical Republicans who saw that Southern Democrats might be willing to compromise more representation in order to subdue the black vote. Representative John A. Bingham proposed an amendment that would enable congress to safeguard “equal protection of life, liberty, and property.” It was denied in 1866. A combination of these two proposals with provisions for Confederate debt and representatives was later suggested, which garnered passage in the House and the Senate with some amendments.