The Enduring Legacy of Andrew Young

Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young in 1965

Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young in 1965

For ArthurAshe.org’s final Black History Month installment, we turn our attention to Andrew Young. Truly a renaissance man, Young has worked as an activist, ambassador, politician, philanthropist and pastor.

Born March 12, 1932 in New Orleans, Louisiana during segregation, his mother Daisy Fuller Young was a schoolteacher and his father, Andrew Jackson, Sr., was a dentist. His family was solidly middle-class, able to afford boxing lessons for him and his younger brother, Walt, which their father initiated so that they would be able to defend themselves. Young attended Dillard Academy for high school, later graduating from Howard University for college with a degree in biology. Originally he had considered following his father into dentistry, however, instead he switched tacks, attending Hartford Seminary and earning a divinity degree in 1955. He was ordained in the United Church of Christ.

While earning his degree, Young also met teacher Jean Childs, who we would marry in 1954. He was assigned first to Marion, Alabama, followed by Thomasville and then Beachton, Georgia. Very interested in Mohandas Ghandhi’s nonviolent resistance movement, he became involved with organizing voter registration drives for blacks, even though he received death threats. He also became acquainted with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at this time.

In 1957 he was called to New York City to work with the National Council of Churches, where he served as assistant director for the Youth Work Division. He joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and in 1961 returned to the South to continue doing voter registration drives and voter education campaigns. He served as a mediator and negotiator for the SCLC during various incidents, including when the Albany, Georgia police arrested King and fellow leader Ralph Abernathy; during the campaign in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, in St. Augustine, Florida in 1964, in Selma, Alabama the following year and in Atlanta, Georgia in 1966.

In 1964 Young was named executive director of the SCLC, from which position he helped gain passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The former outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, thus officially ending segregation in any facility that serves the public as well as setting requirements for literacy tests, which were used to suppress voting. The Voting Rights Act strengthened the provisions from the Civil Right Act and expanded them, enumerating specific policies concerning voting and the administration of elections, banning literacy tests, and requiring certain jurisdictions to gain Justice Department pre-approval before making any changes that would affect voting.

Born March 12, 1932 in New Orleans, Louisiana during segregation, his mother Daisy Fuller Young was a schoolteacher and his father, Andrew Jackson, Sr., was a dentist. His family was solidly middle-class, able to afford boxing lessons for him and his younger brother, Walt, which their father initiated so that they would be able to defend themselves. Young attended Dillard Academy for high school, later graduating from Howard University for college with a degree in biology. Originally he had considered following his father into dentistry, however, instead he switched tacks, attending Hartford Seminary and earning a divinity degree in 1955. He was ordained in the United Church of Christ.

While earning his degree, Young also met teacher Jean Childs, who we would marry in 1954. He was assigned first to Marion, Alabama, followed by Thomasville and then Beachton, Georgia. Very interested in Mohandas Ghandhi’s nonviolent resistance movement, he became involved with organizing voter registration drives for blacks, even though he received death threats. He also became acquainted with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at this time.

In 1957 he was called to New York City to work with the National Council of Churches, where he served as assistant director for the Youth Work Division. He joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and in 1961 returned to the South to continue doing voter registration drives and voter education campaigns. He served as a mediator and negotiator for the SCLC during various incidents, including when the Albany, Georgia police arrested King and fellow leader Ralph Abernathy; during the campaign in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, in St. Augustine, Florida in 1964, in Selma, Alabama the following year and in Atlanta, Georgia in 1966.

In 1964 Young was named executive director of the SCLC, from which position he helped gain passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The former outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, thus officially ending segregation in any facility that serves the public as well as setting requirements for literacy tests, which were used to suppress voting. The Voting Rights Act strengthened the provisions from the Civil Right Act and expanded them, enumerating specific policies concerning voting and the administration of elections, banning literacy tests, and requiring certain jurisdictions to gain Justice Department pre-approval before making any changes that would affect voting.

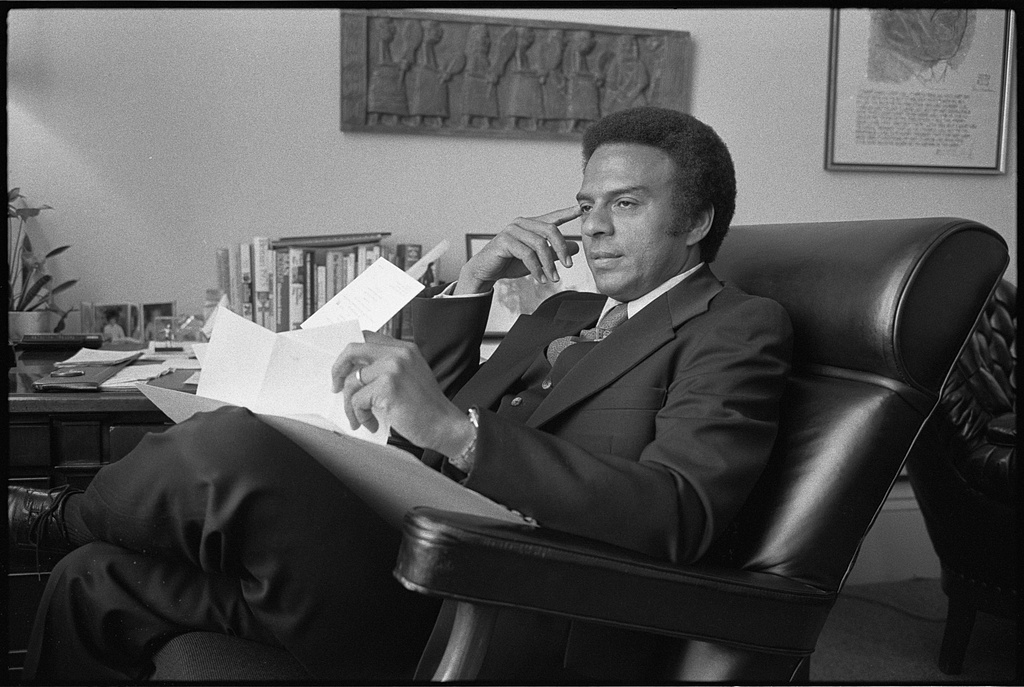

While U.N. Ambassador, Young at the Foreign Relations subcommittee on African Affairs. Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran.

While U.N. Ambassador, Young at the Foreign Relations subcommittee on African Affairs. Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran.

In 1970, Young decided to run for a seat in the House of Representatives. He resigned his position at the SCLC, remarking that, “There just comes a time when any social movement has to come in off the street and enter politics.” The district had recently been reapportioned to increase the number of black voters. Young sought support from those constituents as well as liberal voters and labor voters, calling it the New South Coalition. After winning the Democratic primary, he lost to the incumbent Republican candidate, Fletcher Thompson, in the general election.

In 1972 he ran again, while Thompson ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Advocating for educational improvements and against additional highways and development by the Chattahoochee River, he won the three-way Democratic primary and then the general election, becoming the first African-American Representative from the State since Reconstruction.

Upon arriving in Congress as part of the same freshman class as Barbara Jordan of Texas, he joined the Congressional Black Caucus and became known as a liberal, rejecting spending cuts that would affect the poor and supporting legislation to help the black community. He helped push forward the Urban Mass Transportation Assistance Act, a federal program to help cities build mass transit, such as MARTA in Atlanta. Despite his commitment to liberal policies, he was also good at reaching across the aisle, talking one-on-one with adversaries to try to find common ground. For instance, he supported Gerald Ford becoming President Richard Nixon’s replacement Vice President, describing how, “I decided that here was a guy I wanted to give a chance. He was certainly better than a Reagan or any of the other alternatives at the time. Besides, Atlanta was going to need to work very closely with the next administration.”

Young was also very attuned to foreign affairs, especially issues having to do with colonies and newly independent nations in Africa and Asia. He presented a bill to prevent government contracts from going to companies that practiced discrimination in South Africa under apartheid. He also worked with Republicans to add an amendment to legislation that allowed the President to stop aid to Portugal that might be used for military action in its African colonies, which it was fighting to hold on to. In addition, he also made congressional trips to South Africa, Zambia, Kenya and Nigeria.

Young won reelection in 1974 with 72% of the vote. The following year, he successfully argued for the House to extend the Voting Rights Act of 1965, saying that, “There was a time, when, in order to be elected from our part of the country, you had to present yourself at your worst,” giving as an example that, “The man who was the chairman of my campaign…had to run as a segregationist when he wanted to run statewide.” Making the case for how effective the act had been in increasing black voter turnout and increasing the number of black elected officials in the South, the measure was approved by the House, 341 to 70.

In 1976, Young again won reelection, this time with 80% of the vote. Over the years he had become close to President Jimmy Carter, with whom he shared a deep interest in human rights issues, after first meeting him when he was governor of Georgia. During Carter’s presidential campaign (also in ’76), he had helped organize voter registration drives in urban areas to increase his base of support and delivered a speech for him at the Democratic National Convention. President Carter offered him the position of serving as Ambassador to the United Nations, which Young accepted, resigning from Congress.

Young became the first African-American to hold that position, where he drew upon his significant skills of mediation, such as helping with the Egypt-Israel Peace Talks. however, he also took some controversial stances. At one point, he compared the treatment of political dissidents in the Soviet Union to ones in the United States, making the case that some civil rights and anti-war activists were imprisoned here. He also helped the Rhodesian (now Zimbabwe) government negotiate with leaders of the rebellion there, after a disputed election. In 1979 he met with Zehdi Terzi, U.N. representative for the Palestinian Liberation Organization, a group that the U.S. had stated it would not meet with until they acknowledged Israel’s right to exist. When the meeting came to the attention of the public, he was forced to resign. While he was serving as U.N. Ambassador, he also officiated the wedding of Arthur Ashe to Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe in 1977.

Young lectured at universities and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981 from President Ronald Reagan. That same year, he decided to run for mayor of Atlanta having been encouraged to do so by many people, including Martin Luther King’s widow Coretta Scott King. Young won with 55% of the vote. As mayor he continued to support issues involving education and minorities with programs such as the Dream Jamboree College Fair, which tripled the number of college scholarships going to public school graduates in the city. He also expanded a program started by his predecessor to increase the number of minority and female-owned businesses competing for and receiving city contracts. Due to term limits, he could not run for a third term, but did note his satisfaction to, “be mayor of this city, where once the mayor had me thrown in jail.”

After Young’s tenure as mayor, he ran for governor of Georgia in 1990 in a crowded field. After he lost, he once again turned his attention to human rights, becoming very involved with public policy and philanthropic efforts. Among many activities, he: serves as a director at the Drum Major Institute, a progressive think tank that fights poverty, racism and militarism/violence; was president of the National Council of Churches for a period; founded the Andrew Young Foundation to promote education, health, leadership and human rights in the U.S., African and the Caribbean; in addition to other nonprofit and consulting work. He has written about his experiences fighting for civil rights in two books. Multiple programs exist in his name, including the Georgia State University Andrew Young School of Policy Studies and the Morehouse College Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership. Throughout his life, he has displayed a passion for serving the public and bettering the world. He has also worked to share that passion and encourage others, using education as platform for empowerment. His philosophy can perhaps best be summed up in his own words: “We think it is complicated to change the world. Change comes little by little. Nothing worthwhile can happen in one generation.”

In 1972 he ran again, while Thompson ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Advocating for educational improvements and against additional highways and development by the Chattahoochee River, he won the three-way Democratic primary and then the general election, becoming the first African-American Representative from the State since Reconstruction.

Upon arriving in Congress as part of the same freshman class as Barbara Jordan of Texas, he joined the Congressional Black Caucus and became known as a liberal, rejecting spending cuts that would affect the poor and supporting legislation to help the black community. He helped push forward the Urban Mass Transportation Assistance Act, a federal program to help cities build mass transit, such as MARTA in Atlanta. Despite his commitment to liberal policies, he was also good at reaching across the aisle, talking one-on-one with adversaries to try to find common ground. For instance, he supported Gerald Ford becoming President Richard Nixon’s replacement Vice President, describing how, “I decided that here was a guy I wanted to give a chance. He was certainly better than a Reagan or any of the other alternatives at the time. Besides, Atlanta was going to need to work very closely with the next administration.”

Young was also very attuned to foreign affairs, especially issues having to do with colonies and newly independent nations in Africa and Asia. He presented a bill to prevent government contracts from going to companies that practiced discrimination in South Africa under apartheid. He also worked with Republicans to add an amendment to legislation that allowed the President to stop aid to Portugal that might be used for military action in its African colonies, which it was fighting to hold on to. In addition, he also made congressional trips to South Africa, Zambia, Kenya and Nigeria.

Young won reelection in 1974 with 72% of the vote. The following year, he successfully argued for the House to extend the Voting Rights Act of 1965, saying that, “There was a time, when, in order to be elected from our part of the country, you had to present yourself at your worst,” giving as an example that, “The man who was the chairman of my campaign…had to run as a segregationist when he wanted to run statewide.” Making the case for how effective the act had been in increasing black voter turnout and increasing the number of black elected officials in the South, the measure was approved by the House, 341 to 70.

In 1976, Young again won reelection, this time with 80% of the vote. Over the years he had become close to President Jimmy Carter, with whom he shared a deep interest in human rights issues, after first meeting him when he was governor of Georgia. During Carter’s presidential campaign (also in ’76), he had helped organize voter registration drives in urban areas to increase his base of support and delivered a speech for him at the Democratic National Convention. President Carter offered him the position of serving as Ambassador to the United Nations, which Young accepted, resigning from Congress.

Young became the first African-American to hold that position, where he drew upon his significant skills of mediation, such as helping with the Egypt-Israel Peace Talks. however, he also took some controversial stances. At one point, he compared the treatment of political dissidents in the Soviet Union to ones in the United States, making the case that some civil rights and anti-war activists were imprisoned here. He also helped the Rhodesian (now Zimbabwe) government negotiate with leaders of the rebellion there, after a disputed election. In 1979 he met with Zehdi Terzi, U.N. representative for the Palestinian Liberation Organization, a group that the U.S. had stated it would not meet with until they acknowledged Israel’s right to exist. When the meeting came to the attention of the public, he was forced to resign. While he was serving as U.N. Ambassador, he also officiated the wedding of Arthur Ashe to Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe in 1977.

Young lectured at universities and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981 from President Ronald Reagan. That same year, he decided to run for mayor of Atlanta having been encouraged to do so by many people, including Martin Luther King’s widow Coretta Scott King. Young won with 55% of the vote. As mayor he continued to support issues involving education and minorities with programs such as the Dream Jamboree College Fair, which tripled the number of college scholarships going to public school graduates in the city. He also expanded a program started by his predecessor to increase the number of minority and female-owned businesses competing for and receiving city contracts. Due to term limits, he could not run for a third term, but did note his satisfaction to, “be mayor of this city, where once the mayor had me thrown in jail.”

After Young’s tenure as mayor, he ran for governor of Georgia in 1990 in a crowded field. After he lost, he once again turned his attention to human rights, becoming very involved with public policy and philanthropic efforts. Among many activities, he: serves as a director at the Drum Major Institute, a progressive think tank that fights poverty, racism and militarism/violence; was president of the National Council of Churches for a period; founded the Andrew Young Foundation to promote education, health, leadership and human rights in the U.S., African and the Caribbean; in addition to other nonprofit and consulting work. He has written about his experiences fighting for civil rights in two books. Multiple programs exist in his name, including the Georgia State University Andrew Young School of Policy Studies and the Morehouse College Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership. Throughout his life, he has displayed a passion for serving the public and bettering the world. He has also worked to share that passion and encourage others, using education as platform for empowerment. His philosophy can perhaps best be summed up in his own words: “We think it is complicated to change the world. Change comes little by little. Nothing worthwhile can happen in one generation.”