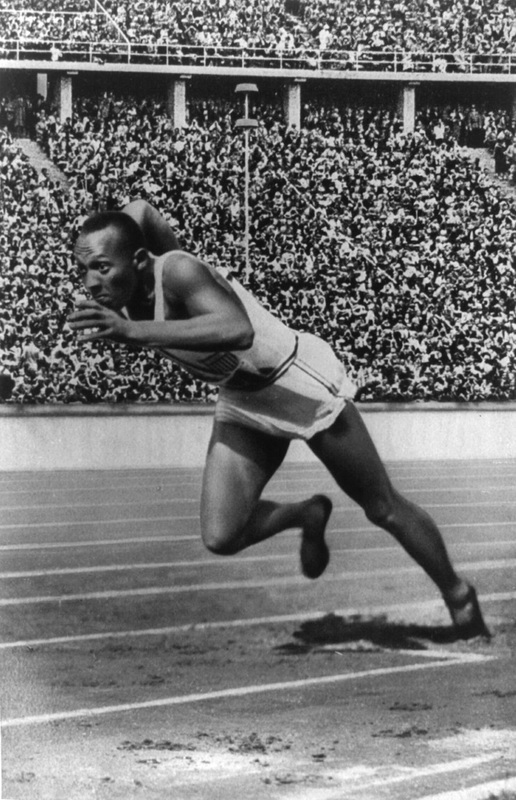

A Black Star: Jessie Owens at the 1936 Berlin Olympics

Born James Cleveland Owens on September 12, 1913 in Oakville, Alabama, Owens became a star in track and field events during his adolescence, setting the stage for his later success. Owens won three track and field events at the 1933 National Interscholastic Championships and led Leads East Technical High School to win the championships with thirty points to his name. While in high school, Owens set the national high school record for the long jump and the 100 and 200 yard dashes, garnering attention nation-wide.

After graduation, Owens matriculated at Ohio State University, which was segregated at the time and a topic of the black press because of its blatant prejudice. Once enrolled, Owens was forced to live in a cramped boarding house apartment with other black students because on-campus housing was not available for them. Despite the racism, Owens went on to win eight individual NCAA championships during his time there, four in 1935 and four in 1936. The only other time any athlete has won four championships was recently in 2006, when Xavier Carter won four national track and field titles. Under the guidance of Larry Snyder, the track team’s coach, Owens shocked the world during the 1935 Big Ten Track meet when he set world records in the 100 yard dash and the long jump at 26-8 ¼ feet. His long jump record would hold for twenty five years until 1960, when Ralph Boston broke the 27 feet barrier.

At the Olympic Games in Berlin, Owens’ achievements shook Adolf Hitler. In addition to using the games as a showcase for the new German government, they were also intended to prove Hitler’s assertions about the superiority of the Aryan race. Owens single-handedly winning four gold medals and beating Lutz Long, the German athlete competing in the long jump, handily dispelled those notions. Owens is known for his superb performance at the 1936 Berlin Olympics and for being the most accomplished athlete of the era. After Owens set the Olympic record for the 100 meter dash, Hitler stormed out of the stadium infuriated.

Unfortunately, the racism did not end in Germany and continued back home: traditionally, the President meets with every gold medalist and invites them to the White House, however, Franklin Delano Roosevelt did not hold that ceremony for Owens. Recalling the entire episode, Owens stated, “Although I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President either.”

After Owens’ success at the 1936 Olympics, he decided to retire from running track and earn money in other competitions, like racing cars and horses. In 1950, Owens was named the “Athlete of the Half-Century” and is regarded today as one the best athletes–and the best track athlete–of the twentieth century. The Jesse Owens Award, the highest award for a track runner, is given annually by USA Track and Field to the best track athlete. While watching the current Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, it is important to remember the athletes who paved the way for today’s generation. Jesse Owens achieved impressive feats in track and field on the world stage that defied racist beliefs. As Arthur Ashe noted, “The victories of black Americans at Berlin serve as a beacon for all Americans of African descent.”